Overview of the Series

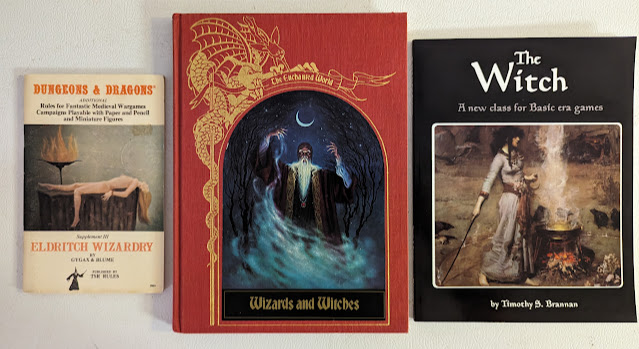

The Enchanted World books from Time-LIFE were a series of high-quality, hardcover books sent to you via mail from Time-LIFE subscription. The first one you got for free was Wizards and Witches. This also makes it the most common one and the one you can find in most secondary markets. Fortunately for me, it was also my favorite.

Imagine, if you can, a time when one of the world's largest publishers decided to invest in a series of books (21 in total) filled with full-color art, cloth-bound covers, and access to some of the world's greatest libraries and scholars. Libraries like the Bodleian Library at Oxford, Cambridge Library, and the London Library. Scholars like Prof. Tristram Potter Coffin (Chief Series Consultant), Ellen Phillips (Series Director and Editor), and Prog. Brendan Lehane (author of this volume).

Well, that time was 40 years ago, and the Enchanted World series sought to capitalize on the growing fascination with all things fantasy, not in a small part due to the popularity of Dungeons & Dragons.

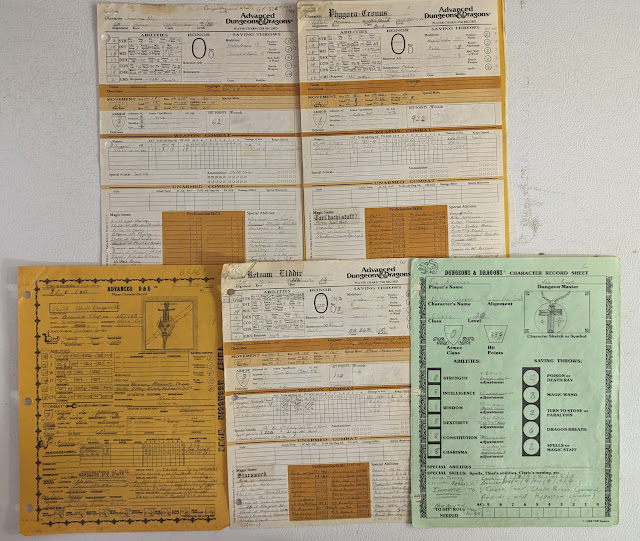

Over the years, I have seen a lot of collections of other folks' RPG books. It is no surprise when you see one or more of these books stuck in their mix of FRPGs.

Many of the books follow a similar pattern. Usually, 3-4 chapters of the book detail different aspects of the myths and folklore being covered. These are usually interspersed with some of the stories themselves or excerpts, as well as art. The art is often from classical sources or paintings depicting the stories or characters involved. There are also new pieces of art throughout. There are margin notes or marginalia with some other related tidbit of information. Each chapter ends with a longer story.

There is a bibliography, art credits, and some publication notes in the back.

These books were published around the world. Some of the European publications also had dust covers.

Wizards and Witches

by Brendan Lehane, 1984 (144 pages)

ISBN 0809452049, 0809452057 (US Editions)

This book is divided into three sections covering ancient wizards, wizards of the Middle Ages, and witches. There is quite a lot of art from Arthur Rackham here.

Chapter One: Singers at the World's Dawn

Here, we begin with a tale of the old Finish wizard Väinämöinen and the young upstart Joukahainen in what could be considered a magical sing-off. The line between Bard and Wizard was very thin in ancient Finland. Thus it was when the world was young and youth could aspire to wizardry. We learn of other powerful names like Volga Vseslavich, Cathbad, Manannan Mac Lir, Taliesin, and, most well-known of all, Merlin. Not all were old men. Ceridwen, Circe, and Louhi were there too.

The thesis here is that in those olden days magic was something people could aspire too, but few could truly master. We get snippets of stories of all these wizards and sorceresses, each playing into the next. It is somewhere between a bedtime story and an undergraduate survey of various wizards. In between we get longer stories, like the "Wizard of Kiev" and "The Welsh Enchanter's Fosterling." All cover magic in a semi-forgotten age that seems to have one foot in history and another in mythology.

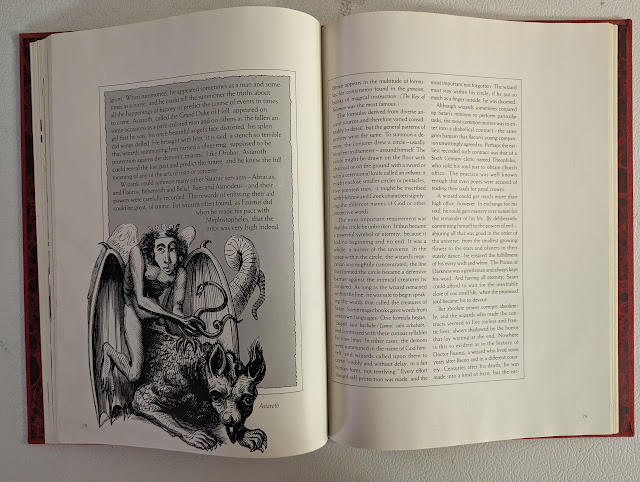

Chapter Two: Masters of Forbidden Arts

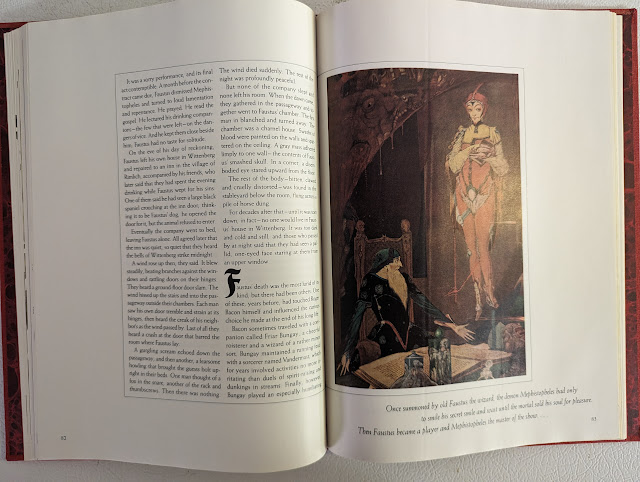

If the last chapter dealt with magical using men and women as heroes as often as villains, then this chapter leaves no ambiguity on where it sees (or rather history sees) the wizard of the Middle Ages. Here the singing battles of Bard-Wizards are given way to the academic study of magic in dusty tomes of forgotten lore and those who sell their very soul for power. We encounter the likes of Roger Bacon (1219-1292), Oxford Scholar, Empirical Philosopher, Franciscan friar, and dabbler in magic. There is even a bit on Michel de Nostredame (1503-1566) aka Nostradamus. But for the most part we see magic going from a force of nature in a world where the rules are not yet set in stone, to men (for the most part) partaking in deals with demonic or devilish figures for power. All it takes is their soul.

We spend quite a bit of time on the legend of Faust and his deal with Mephistopheles. In fact, this one is so set into our vernacular that a "Faustian Deal" hardly needs any explanations.

Given the time period, there is also a wonderful overview of the Tarot and its origins with some rather fantastic art.

But most of all I loved the "Legions of the Night" section with its coverage of Demons. The descriptions of just the few here and the art by Louis Le Breton from the Dictionnaire Infernal by Collin de Plancy were enough to make me want even more strange demons in my game. More so since it featured Astaroth. A demon that already fascinated me from when I first saw him in Best of Dragon II.

Along with the Tarot, there is some coverage on astrology. This predates the Middle Ages by, well, thousands of years really, but there was new keen importance on it at this time.

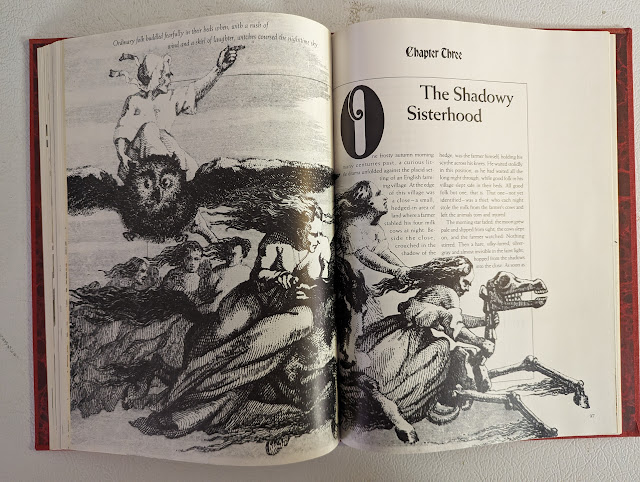

Chapter Three: The Shadowy Sisterhood

Ah. Here are my witches. We get some cover on what could be called Folk Magic or Hedge Witchery, on how these natural healers were initially an important part of everyday life. The magic was simpler and more in tune with nature.

Throughout this chapter, the "helpers" of witches are mentioned. We call them Familiars. Up first is the hare, which they claim (and back up) was closer to the witch than the black cat we associate with today. This reminds me that rabbits and hares should really feature more in my games. The others include spiders, ravens and crows, cats, snakes, and toads, which they claim as one of the first animals to be associated with witches. I have read that before as well.

As the chapter professes the old Black Magic vs. White Magic trope appears. While less in favor today among Real WitchesTM (remember the ads with Litney Burns?) it is an important distinction of the time. It is almost the same divide as the "Natural" vs. "Academic" wizards of the first two chapters, really.

There are various stories, mostly about how someone was suspected of witchcraft and what happened. But also the machinations of witches in general.

There is a section flight and witches and how brooms were not used at first, but rather things like butter churns and distaffs. I even added distaffs to my games in part because of this connection.

Our story at the end of this chapter is a classic tale of Baba Yaga and Vasilsa the Fair. Again featuring amazing artwork, this time right from Vasilisa the Beautiful by Ivan Bilibin.

Use in FRPGs

With so many books out there, there is no end to the ideas they can generate. Upfront, it should be noted there is nothing "new" here. The stories, the folklore, and even a lot of the art are things we have all seen before. The stories of wizards like Väinämöinen, Merlin, Faust, and Circe should all be known to anyone who has a passing interest in fantasy and, indeed, to anyone who has played FRPGs. But that is not where their value lies. These books do have tidbits that the causal pursuer of these tales would not know, and maybe even some for the more advanced students.

To be sure, while there is academic rigor here, these are not textbooks. But they are educational.

Reading these tales one could use them as the basis for other characters. There is more than just a little bit of Taliesin in my own Phygora, for example. These tales, often set right on top of each other, can give the reader and player plenty of means of comparison.

This book also makes good arguments for the separation between, say, Wizards, Warlocks, and Witches (as represented by the three chapters) but less of an argument on where bards fit in. Are Taliesin and Väinämöinen wizards or bards, for example? It is not up to this book to decide but rather the reader.

If you are playing a game like D&D that lives in a different world, then ideas abound. I mean we know Gygax, Arneson and the early designers of the game were very much into folklore and mythology. Those elements are the hook for more of these, beyond the Greek, Roman, and Norse myths we were all raised on. Like any good synthesis, it should make you want to check out the primary stories these are all from. If you are playing a Medieval game, say Chivalry & Sorcery or Pendragon, then this is practically a sourcebook for you. I would even say it is a must-have for a Mage: Dark Ages or Mage: Sorcerers Crusade game.

Witches

I can't let it go unsaid, even if it is obvious, but this book profoundly affected me when it was out. While I did not own my own copy until much later on, I had friends that had it. Since this was the first of the series, many people had it. The art in this book set the feel for how I wanted my Witch class books to look. I have since included the art of Arthur Rackham and the Pre-Raphelites in many of my books. This was one of the books that made me want a witch book for D&D. When none showed in the stores I took it on myself to make it. I do know that my first encounter with the "Black School" of the Scholomance was from this book.

While I can't say with any certainty other than the timeline, this book was likely a contributing factor to one of my favorite themes in games; Pagans vs. Christians and how magic would later be demonized by the Church.

This series is lovely, and each book, while filled with things I already knew, also has many things I did not.

My only real complaint? At 12.25" x 9", they just don't fit nicely into a standard bookcase.

Next Time: What is love?